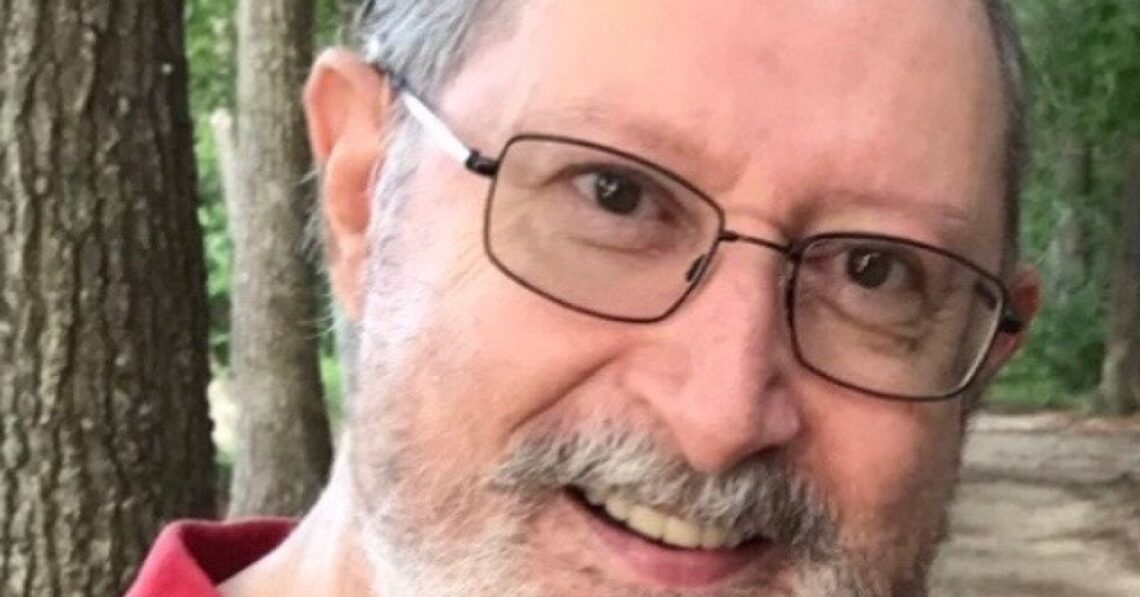

John Kline is a good friend of mine, who I met through the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Connection Support Group program. We’ve been facilitating a local NAMI support group together for years. He has a captivating story of experiencing Bipolar I, psychotic breaks, and what emotional recovery looks like. He also tells the story of his prolific career as a paramedic, and how his experience of bipolar shaped his career and his personal life.

Sarah Merritt Ryan: How did your illness start and when were you diagnosed?

John Kline: I was diagnosed as schizophrenic when I was 18 years old, during my first semester of college when I was brought home after having a psychotic break. I was slipped some LSD in my beer when I wasn’t looking. In the emergency room, I was comatose, basically: I didn’t know who I was or where I was, and when my mom finally got into the room, I don’t even think I recognized her.

The LSD trip precipitated my illness, but I probably would have eventually had that episode at school anyway, as my dad had real bad bipolar. I was treated with schizophrenic medications for about four years until I was re-diagnosed with Bipolar I.

SMR: You’ve dealt with partial breaks throughout your life that must have been so frustrating. How did you process these, and what did you do about them?

JK: After those two breaks, I would have partial breaks. Not a complete psychotic break, where you need to be in the hospital, but I would have, I guess you call, partial nervous breaks or nervous breakdowns, where I was not very functional. I really couldn’t go to work and couldn’t socialize. I would be house bound.

Every time I had these breaks or these nervous breakdowns, I had a burning anger that this is happening over and over every year and a half, almost like clockwork. I had to do something about it.

SMR: Explain your big break professionally and the work you put into becoming a paramedic.

JK: I was working full time as an EMT on the graveyard shift, on the ambulance, and was going full time days to paramedic school for two years. I was still having bipolar episodes, but they were pretty subdued. I was getting treated, and I knew how to handle them and take time off when I needed to.

I graduated, and I was one of the first 100 paramedics certified in the state of New Jersey. It became my mission. It became my thing to save lives. In my career, I responded to more than 10,000 calls.

After the heartbreak of having a serious mental illness and not doing well in numerous jobs, I was actually now doing something that gave me confidence, tremendous pride, and a sense of belonging in a tight knit community.

SMR: How did you accommodate for your illness professionally?

JK: When I started as an EMT, I felt that bipolar episodes were probably going to keep coming, because they had never stopped for my whole life. I needed to put some emotional strength in as money in the bank. So, I consciously tried to become the best EMT and eventually the best paramedic that I could possibly be. So, if I ended up having an episode and people say, Well, John doesn’t seem to be acting quite right,” or is a “little off,” I wouldn’t be questioned, because I always did a great job.

SMR: I’ve heard you say your illness both helped you and hurt you on the job. How so?

JK: Bipolar can be a help when you’re working in the rescue service, when you live just a little bit on the manic side of the scale, as opposed to the depressive side of the scale. That bit of mania gave me a little extra sharpness, focus and energy, which is what you need at three in the morning, and what is required to be respected by other first responders and by the public. So bipolar, in that respect, helped me. I had so many traumatic calls, I developed PTSD. When depression from bipolar and PTSD combined occasionally, it made the job harder.

SMR: Was there stigma for your illness in the workplace?

JK: There was. When I was working civilian jobs, I might mention to somebody that I was bipolar, and a lot of times the word would spread among whoever I was working with, and it would get back to the boss. And sure enough, I’d find myself fired pretty rapidly after that. Or I could show symptoms of having a bipolar episode of depression or mania, where I could come across as too elated at work.

SMR: In your memoir, Heart of Rescue: A Bipolar and PTSD Self-Help Memoir, available on Amazon under the pen name John Towns, you offer insight for others with bipolar. What would you say to someone else struggling with a chronic mental illness at a young age?

JK: I would say, go ahead, keep living your life. No matter what, still try to live and relish it. Try to appreciate the good, and when the bad happens, make sure you get help, whether it’s from friends, family, or professionals. Get help that enables you to live an even better life. As you improve, you’re going to find things are more satisfying. If you find your passion or something you want to dedicate your life to, you will experience joy in your life.

SMR: If someone is struggling with emotional pain and hopelessness from mental illness, what would you say?

JK: Well, even though not being religious and not having read very much of the Bible, I remember that phrase “to every thing there is a season.” Whatever illness you have or whatever bad times you’re suffering from, you have to realize that it will eventually pass. It gives you something to look forward to in the depths of despair or whatever the worst feelings are that you’ve had in your life.

SMR: How do you pay it forward in terms of your life experiences?

JK: Now, I have two missions of my life. The first one is to give aid if and when I see it’s needed somewhere. That could be stopping for an accident if no first responders have arrived yet and providing help. My other mission now is working with the National Alliance of Mental Illness as a support group facilitator to help other people with mental illness.